[mc4wp_form id=”2320″]

Africa's Economies Feel Pain of Cybersecurity Deficit

-

August 21, 2024

- Posted by: Evans Asare

Africa’s economies feel pain of cybersecurity deficit, while the combined gross domestic product (GDP) of African nations grew fivefold in two decades, a lack of cybersecurity is holding back gains — although the jury is out on how much.

As Africa experiences fast economic growth, cybercrime appears to be keeping pace.

In 2023, for example, the average number of weekly cyberattacks impacting African businesses grew 23% compared to the prior years, the fastest increase worldwide, according to Interpol’s 2024 African Cyberthreat Assessment, with ransomware and business email compromise (BEC) topping the list of serious threats. Digital illiteracy, aging infrastructure, and a lack of security professionals all present challenges to preventing economic loss due to cybercrime, according to a report published last month by Access Partnership and the Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria.

As the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) grows to an estimated $4 trillion by 2027, cyberattacks and cybercrime constitute a significant drag on economic development, and African nations need to accelerate their training of cybersecurity skills, says Nicole Isaac, vice president of global public policy for technology giant Cisco.

“Africa faces the most significant impact from cyber threats compared to any other continent,” she says, adding “nearly [all] financial leaders in Africa consider cybercrime a significant threat along with macroeconomic conditions and political and social instability.”

Read more: Africa Data Centers and Onix Data Center announce partnership.

Currently, Africa accounts for eleven of the world’s top-20 fastest growing economies, with Niger, Senegal, and Libya leading the region’s strong economies with growth rates of at least 7.9%, according to the African Development Bank Group. South Africa, Nigeria, and Egypt are the three largest economies in the region, but none have signed the Malabo Convention, the cybercrime protocols put forward by the African Union.

South Africa, for one, has seen cybercrime cost the economy around 2.2 billion Rand per year (US $123 million), much of it made possible by the general lack of cyber-safety knowledge, says Heinrich Bohlmann, associate professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

Cybercrime is often the result of users at home and at work being unaware of cyber risks and scams, he says. “They too easily click or reply to things they shouldn’t, and in the workplace, this can, of course, have massive repercussions for businesses.”

A Teaching Moment

The rising cost of cybercrime should be considered an opportunity, especially as Africa embarks on its digital transformation. While many western and Asian populations are aging rapidly, Africa is seen as a source of young, tech-savvy workers in the future, who will be well situated to use new technologies, such as AI for business and to improve cybersecurity.

African nations will have to advance quickly and develop collaborative relationships just as fast, says Caroline Parker, managing director in FTI Consulting’s South Africa financial communications practice.

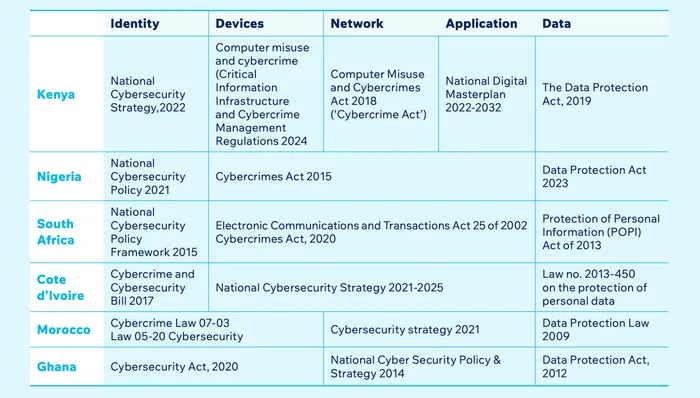

“It is essential that governments put the requisite guardrails in place by developing robust regulatory frameworks to enhance cybersecurity best practice,” she says. “This cannot be an isolated response from individual governments given how portable the problem is across borders, therefore, harmonization of standards and regulations is required on a regional basis.”

AI could help bring a lot of changes to Africa, with the economic value of AI in sub-Saharan Africa expected to create more than US $130 billion in growth, according to Access Partnership and the University of Pretoria’s “Elevating Africa’s Cyber Resilience” report. It has the potential to empower under-represented groups, providing them with the skills and opportunities needed to safely participate in the digital economy, Cisco’s Isaac says.

“AI systems can significantly enhance human capabilities in threat detection and incident response through machine learning and deep learning techniques,” she says. “They can also simplify cybersecurity operations by automating routine tasks such as malware detection and vulnerability assessment.”

Need for Better Cybercrime Data

The reports and estimates also underscore the need for better data on the problem of cybercrime, as current estimates typically do not have supporting evidence and appear to be overinflated. For example, one data point in the “Elevating Africa’s Cyber Resilience” report posits that cybercrime will cost African economies 10% of GDP. The UN Economic Commission of Africa cites the 10% figure as well. Neither report has supporting data.

In reality the cost is likely 30 times less. Estimates of the cost of cybercrime in Africa typically vary between $4 billion and $10 billion per year. With the current GDP of Africa estimated at $2.81 trillion by the International Monetary Fund, the largest cost of cybercrime ends up around 0.3% of GDP.

The data really has not been well-explored, says the University of Pretoria’s Bohlmann.

“For Africa as a whole, [the cost] could be anything,” he says. “However, the 10% of GDP equating to US $4.12 billion is clearly a typo or mistake.”